What Voyager 1 Just Pulled Off at 15 Billion Miles Away

NASA’s Voyager 1, the most distant human-made object in space, just pulled off an astonishing recovery. After 37 years, engineers switched back to its original thrusters—reviving communications across nearly 15 billion miles.

By The Duskbloom Media Team

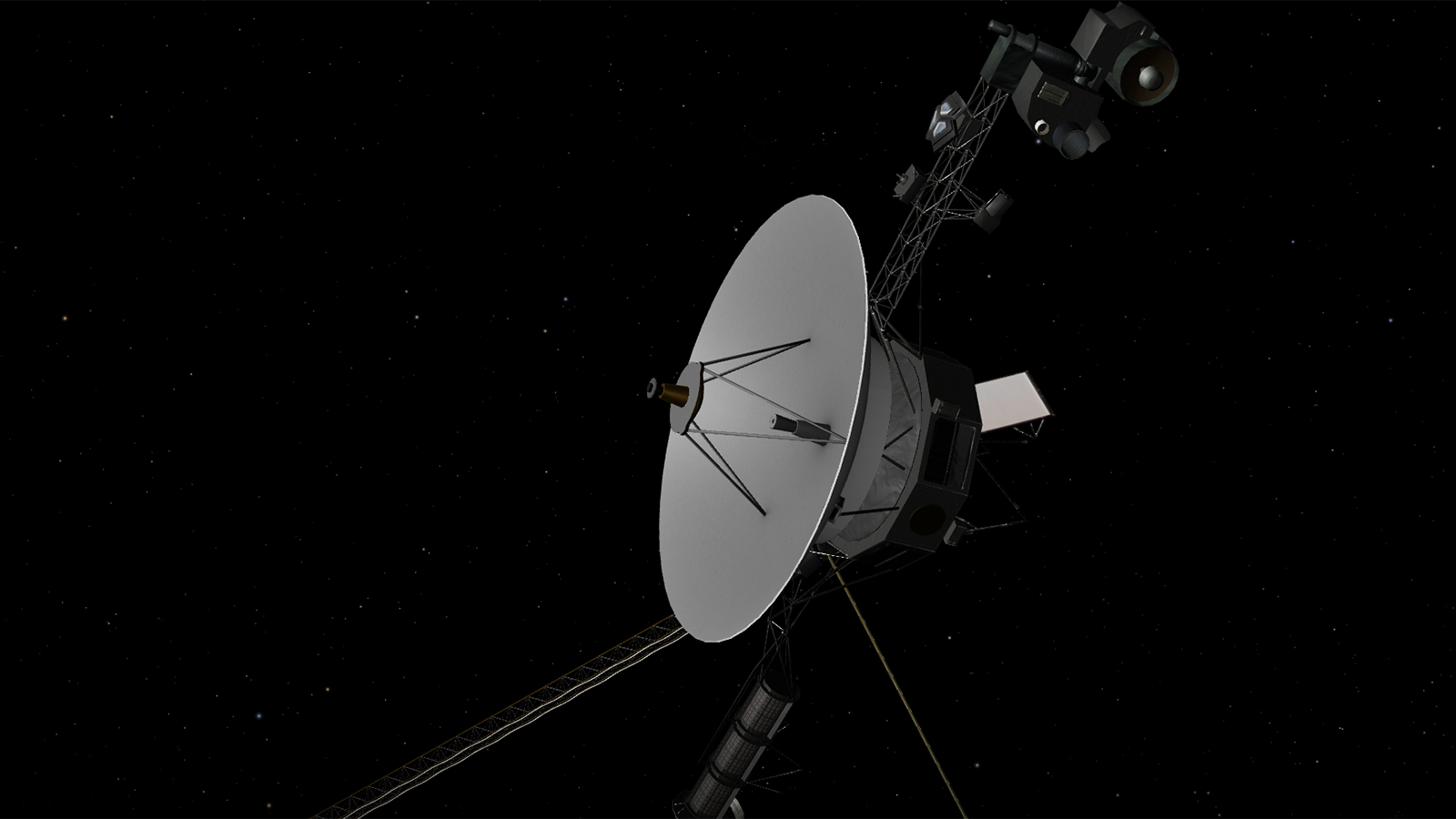

Image via NASA/JPL-Caltech

It sounds like science fiction: a tiny spacecraft launched during the Carter administration, hurtling through interstellar space at 38,000 miles per hour, suddenly goes quiet. Then—after months of silence—NASA engineers send a fix... and it works.

In April 2025, something extraordinary happened. After a long communication blackout, NASA’s legendary Voyager 1 began talking back again. The reason? Engineers at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) managed to switch the spacecraft back to its original thrusters—ones it hadn’t used in 37 years.

This wasn’t just a clever repair. It was a masterstroke of remote engineering, a high-stakes cosmic Hail Mary pulled off from nearly 15 billion miles away—the farthest any human-made object has ever traveled.

Let’s break down how it happened, why it matters, and what it tells us about the limits of persistence, problem-solving, and the aging marvel that is Voyager 1.

First, a Quick Refresher: What Is Voyager 1?

Voyager 1 was launched on September 5, 1977, as part of NASA’s ambitious Voyager program. Its primary mission? To fly by Jupiter and Saturn and send back unprecedented data. But after completing that mission with flying colors, it just kept going—out of the solar system and into the unknown.

In 2012, Voyager 1 crossed the heliopause—the boundary where the solar wind is no longer dominant—officially entering interstellar space. Since then, it’s been sending back data about cosmic rays, plasma waves, and magnetic fields from the edge of the solar bubble.

The spacecraft runs on a radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG), and as of 2025, it's still alive—barely.

The Problem: Silence from the Stars

In late 2023, NASA noticed something wasn’t right. Voyager 1 began transmitting garbled data—essentially nonsense. Telemetry about onboard systems was either missing or indecipherable.

The diagnosis? A fault in the spacecraft’s Flight Data Subsystem (FDS), which formats science and engineering data before it’s sent to Earth. But here's the kicker: any command to fix the problem would take about 22.5 hours to reach the spacecraft, and another 22.5 hours for a response to return.

That’s a 45-hour round trip for every adjustment.

Engineers were essentially conducting brain surgery on a 1970s computer—blindfolded, from across the solar system, using a rotary phone.

The Fix: A 1970s Thruster Comeback

One option was to reboot the FDS entirely, which was risky. But another strategy involved rerouting the data stream—basically bypassing the faulty part of the subsystem.

But first, they had to stabilize the spacecraft's orientation. That's where the thrusters came in.

Voyager 1 has backup thrusters—the trajectory correction maneuver (TCM) thrusters—that had been unused since the flyby of Saturn in 1980. NASA hadn’t fired them in 37 years. No one even knew if they'd still work.

And yet... they did.

In early 2025, NASA engineers successfully fired the TCM thrusters, reoriented the spacecraft, and enabled a new path for data flow.

In April 2025, Voyager 1 successfully transmitted usable engineering data again. The recovery was as astonishing as it was emotional.

Why It Matters

1. Deep-Space Longevity

Voyager 1 was only supposed to last four years. It’s been operational for nearly 48. This fix proves that with enough ingenuity (and luck), even antique spacecraft can be pushed beyond all expectations.

2. Engineering Brilliance

The recovery demonstrates the unmatched patience and creativity of mission engineers. Picture debugging code—but with a 45-hour delay and zero ability to physically interact with the machine.

It’s one of the longest-distance tech fixes in human history.

3. Scientific Goldmine

Voyager 1 remains the only probe sending back real-time data from interstellar space. It’s helping scientists understand cosmic radiation, magnetic fields, and the structure of the heliopause—knowledge that could one day guide human interstellar travel.

What’s Next for Voyager 1?

NASA expects the spacecraft’s RTG power source to last until around 2030. Until then, the mission team will begin powering down nonessential instruments one by one to conserve energy.

There’s no dramatic crash landing planned—Voyager 1 will simply keep drifting in silence, carrying the Golden Record etched with sounds and images of life on Earth.

In about 40,000 years, it will pass near another star system. And who knows—maybe someone or something will find it.

The Takeaway

Voyager 1's latest trick isn’t just a feel-good story about old tech surviving in deep space. It’s a testament to human tenacity and imagination.

At a time when billion-dollar rockets capture headlines, it’s worth remembering: the most remarkable spacecraft of all might be the one that's already 15 billion miles away, still doing its job—against all odds.

Ad Placeholder

Article Inline Ad

Billboard

More from Science

Why Earth’s Magnetic Field Might Be About to Flip (And What That Actually Means)

By The Duskbloom Media Team

Synthetic Embryos Without Sperm or Egg: Are We Rewriting the Origin of Life?

By The Duskbloom Media Team

The Brain’s Hidden Clock: How Time Cells May Reshape Our Understanding of Memory

By The Duskbloom Media Team