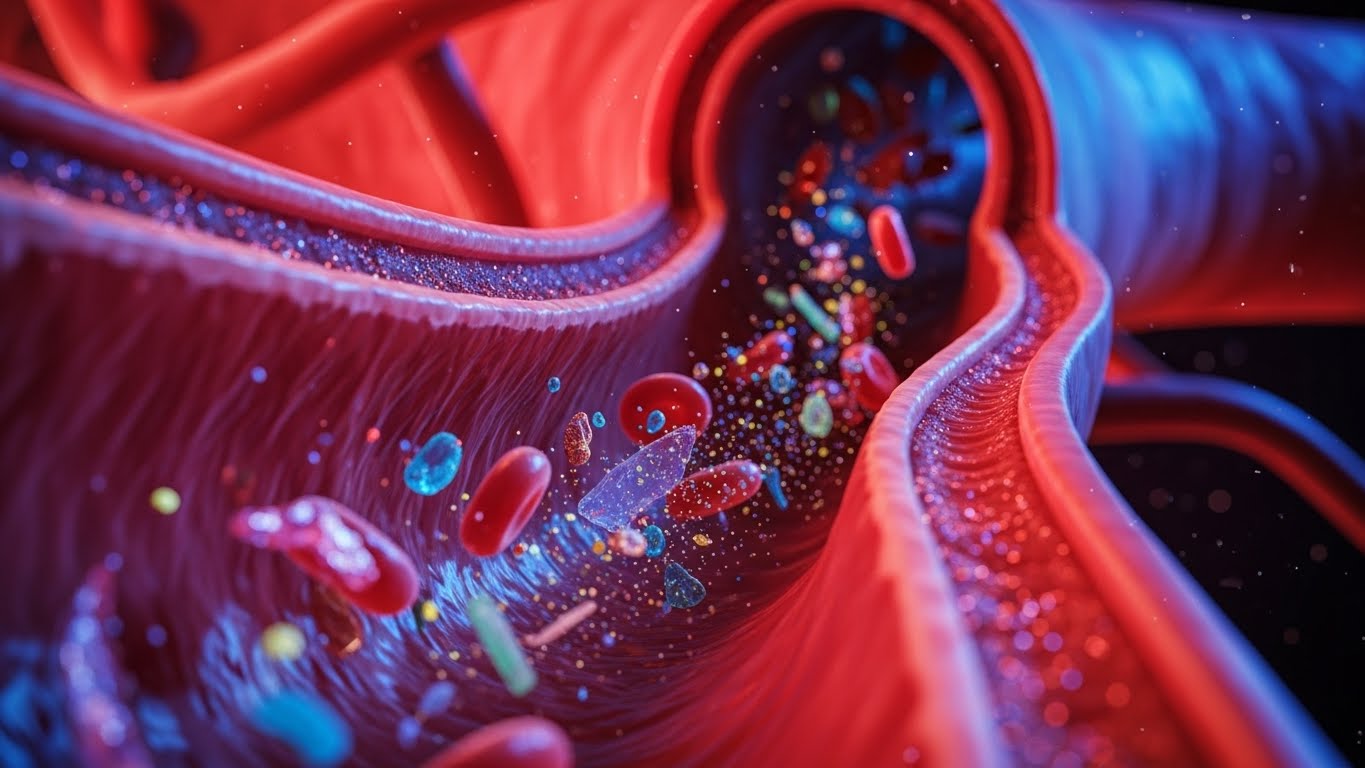

Plastic Dust in Our Arteries? Study Links Microplastics to Higher Heart Risks

A 2024 NEJM study revealed that microplastics in human carotid plaques were linked to higher risks of heart attack, stroke, and death—raising urgent questions about how pollution reaches our arteries.

By The Duskbloom Media Team

Image via Duskbloom Discovery

When vascular surgeons removed plaque from patients’ carotid arteries to prevent strokes, they didn’t expect to find plastic. But high-resolution infrared spectroscopy revealed polymer fragments where only blood and cholesterol should be — polyethylene from packaging and PVC from pipes and flooring.

That discovery, published in the New England Journal of Medicine in late 2024, turned a quiet surgical procedure into a revelation: microplastics and nanoplastics are infiltrating human arteries, and they might be increasing the risk of heart attack, stroke, or death.

The Study That Sparked Alarm

Researchers examined plaque samples from more than 250 patients undergoing carotid endarterectomy, a surgery performed to reduce stroke risk. Using advanced spectroscopic imaging, they found that roughly 60% of samples contained microplastics or nanoplastics, most commonly polyethylene and PVC.

Over nearly three years of follow-up, participants with microplastics embedded in their arterial plaques were 4.5 times more likely to experience a major cardiovascular event — including myocardial infarction, stroke, or cardiovascular death — compared with those whose plaques were plastic-free.

It’s an unsettling finding: the same materials that make up disposable bottles and synthetic textiles may be quietly accumulating in the very tissues that sustain blood flow to the brain.

How Plastic Reaches the Bloodstream

Scientists believe these particles enter the body primarily through air, water, and food. Inhaled microplastics can cross the lung barrier, while ingested ones may pass through the intestinal lining. Once inside, they circulate via the bloodstream, adhering to inflamed or damaged tissues.

Previous studies had already detected microplastics in human blood, lungs, placenta, and even breast milk. But this was the first to show their presence in atherosclerotic plaques — hardened, fatty deposits that form inside arteries.

The mechanisms remain under investigation, but the leading hypothesis is that the particles act as foreign bodies, triggering inflammatory and oxidative stress responses that make plaques more unstable and prone to rupture.

Why This Discovery Matters

Cardiologists have long warned that the environment plays an underappreciated role in heart disease. We know air pollution increases cardiovascular risk; now, microplastics might represent a new category of environmental threat.

The implications go beyond cardiology. If microplastics contribute to vascular inflammation, then tackling pollution becomes a public health intervention as much as an environmental one. Reducing exposure could prevent not just ecological damage, but human disease.

Dr. Raffaele Marfella, the study’s lead author, summarized the shift: “We’ve studied cholesterol for decades, but it’s time to recognize the pollutants we carry inside us.”

What We Still Don’t Know

Despite the striking correlation, the study cannot prove causation. It included high-risk patients already undergoing vascular surgery, and it’s unclear whether microplastics caused the observed cardiovascular events or were simply biomarkers of broader exposure.

Future research will need to answer critical questions:

- How long do plastics remain in vascular tissue?

- Are some polymers more biologically reactive than others?

- Can we measure exposure accurately in living patients?

Regulators and scientists are already moving: the European Food Safety Authority and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency are funding new projects to study the toxicokinetics of microplastics and their accumulation in human tissue.

Toward a Cleaner Circulatory System

The NEJM study arrives amid growing evidence that modern materials are shaping biology. Plastics were designed to be durable; now that durability is turning into a liability at the microscopic scale. Reducing pollution may one day be viewed as a cardiovascular prevention strategy, not just an ecological one.

For now, clinicians emphasize traditional prevention: balanced diet, exercise, and avoiding tobacco. But environmental cardiology — once a fringe concept — is becoming impossible to ignore. Every sip of bottled water, every inhale of city air, may play a tiny role in vascular health.

Microplastics are everywhere, and, increasingly, they’re in us.

Key Insights

- Microplastics detected in human carotid plaques were associated with a 4.5-fold higher risk of heart attack, stroke, or death over ~3 years.

- Particles included polyethylene and PVC, common in packaging and construction materials.

- Mechanisms likely involve inflammation and oxidative stress, destabilizing arterial plaques.

- Study is observational but highlights a potential new cardiovascular risk factor tied to environmental pollution.

- Further research could redefine heart health as an environmental issue as much as a metabolic one.

Sources: [1] New England Journal of Medicine — “Detection of Microplastics and Nanoplastics in Carotid Artery Plaques and Association with Cardiovascular Events” (2024) [2] PubMed ID 38446676

Ad Placeholder

Article Inline Ad

Billboard